Flareups are a part of providing Endodontic therapy.

Whether it was a classmate in a clinic with us as dental students, a coworker out in private practice, or our own patient, we have all experienced it. A day or two after endodontic therapy, a patient returns to our place of practice in intractable pain, possibly swollen, looking at us with a touch of skepticism. If you haven’t experienced this, either you don’t do endodontic procedures or haven’t performed enough of them. Somewhere in the venn diagram of endodontic treatment that is made up of treatment modality, host response, and bacteria, this situation will face any one of us. While you cannot completely eliminate the occurrence of flareups, there are some specific steps that can assist in reducing the incidence of this untoward event.

Clinically speaking, my focus is on minimizing the extrusion of debris apically, as well as maximal disinfection coronally prior to proceeding in a crown down fashion. While I may quickly pass a small hand instrument to get a “general working length”, I make no effort to obtain patency until I have done a significant amount of shaping coronally, as well as using the EndoActivator liberally. Finally, it’s important for clinicians to understand that the best predictor for postoperative discomfort is preoperative discomfort. Sounds simple, but paying close attention to your treatment protocol, as well as setting the expectations for the patient postoperatively is extremely important.

Postoperative instructions detailing what to expect are an explanation prior to the experience of significant postoperative discomfort. These instructions are an excuse when the first time the patient hears of this is two days later when they haven’t slept.

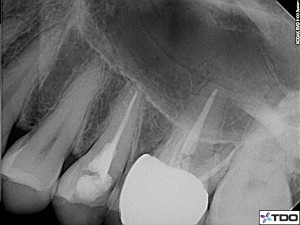

The following case is an example of a case that appeared to be a flareup upon first glance. A 37 year old woman presented to my practice in discomfort. She underwent endodontic treatment on tooth #13 approximately five months prior, however the tooth was not restored at this time. Upon presentation her tooth was sensitive to percussion and palpation, and she had experienced escalating pain over the few days preceding her visit. There was a 5mm periodontal pocket on the distal of tooth #13, and food impaction was clinically evident. Diagnosis for tooth #13 was as follows:

Pulpal: Previously Treated

Periapical: Symptomatic apical periodontitis

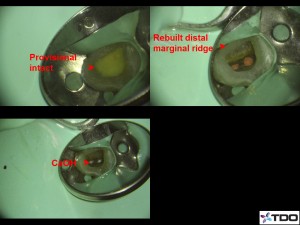

The treatment plan for her tooth involved nonsurgical retreatment with Calcium hydroxide therapy. After determining that we were going to retreat this tooth, we anesthetized the patient. After she was adequately anesthetized, we were able to engage in some brief conversation, and then segued into the topic of her tooth. The discussion involved what to expect during as well as after treatment. In addition, we discussed the potential need for long term Calcium hydroxide therapy in rendering her tooth free from symptoms prior to definitive restoration. During her initial visit, gutta percha was removed and thorough cleaning and shaping of the tooth were performed in conjunction with the use of the EndoActivator and the PiezoFlow. In addition, a composite buildup was used to repair the distal marginal ridge. Calcium hydroxide was placed, the tooth was provisionalized, and the occlusion was adjusted. The patient was prescribed analgesics, and appointed for a follow up visit.

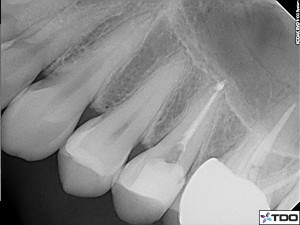

Three days later, the patient presented in a great deal of discomfort. Although her initial “burning” discomfort was starting to improve by day 3, she was still unable to put any pressure on her tooth while functioning. Upon clinical examination, the tooth was sensitive to percussion, but notably, palpation sensitivity was limited to the papilla between #13 and #14. This area was exquisitely sensitive to periodontal probing, so much so that accurate readings were not obtained at that visit. After a brief but thorough discussion, I reasoned that this episode of discomfort was secondary to the healing of the periodontium on tooth #13. The patient was dismissed at this time. Per phone conversation, the patient reported no discomfort at ten days postop and returned approximately two weeks later for an additional visit. On two additional visits the patient was seen to remove and replace Calcium hydroxide. Approximately 6 weeks after initial treatment, the patient was asymptomatic, and the case was obturated.

She was returned to her general dentist to have restorative work completed.

So what can we learn from this case:

1. People who come in with a great deal of discomfort are likely to experience signifcant postoperative discomfort.

2. Providing your patients with a well defined set of expectations for the pre-, peri- and postoperative periods is a benefit to both practitioner and patient.

3. A crown down approach will help reduce periapical extrusion and subsequently periapical inflamamation

4. Periodontal discomfort can occur in conjunction with endodontic and restorative treatment

5. Calcium hydroxide is an underused, but irreplaceable agent in endodontic therapy.

Like so many cases I treat, I look forward to a long term recall on this case.