Sometimes we need to indulge in straight talk. Straight. Talk.

Patients don’t want to feel discomfort and I don’t want them to feel any discomfort. Ever.

Unfortunately, this is not reality as there is some discomfort involved with most endodontic treatment. I’m not saying that people should expect to be in agony. Nor would I suggest that we cannot take specific steps to minimize discomfort during dental procedures. What I want to do is be honest about what goes on during endodontic treatment. Particularly when we are dealing with the patient suffering acute discomfort. I hear many claims of painless dentistry. My goal is minimal discomfort. If you have ever received an injection, some are worse than others, but few people would describe the experience as pleasant.

In a prior post, located here, I addressed my thought process regarding anesthesia. What I want to do here is discuss some my experiences with local anesthesia and provide some techniques that may assist others in obtaining effective anesthesia.

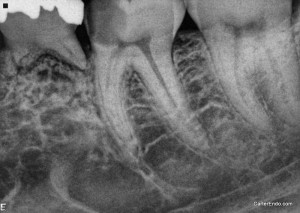

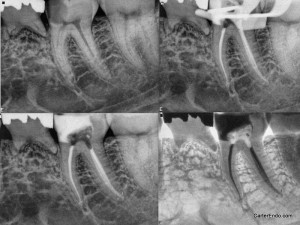

This patient presented in acute discomfort on tooth #19. The diagnosis of this tooth was: Symptomatic irreversible pulpitis, Symptomatic apical periodontitis. This tooth had not been symptomatic for very long, but the discomfort was in an acute phase. I want to discuss how I think about keeping this patient comfortable during treatment.

People who are in pain, particularly acute pain, will often exhibit what I call “noxious stimulus fatigue”. This is not a scientific term that I remember being taught. It is how I describe the condition people are in when they haven’t slept in a couple of days, have been popping Advil, sipping cool water (among other things) and trying to get in to see their dentist for a painful tooth.

These patients often exhibit hyperalgesia, and as such, perceive their experiences in the dental chair very differently from the way the practitioner may. They also often don’t want to talk about anything, they just want to get out of pain. Even if the patient is normally engaging and personable, this condition can really alter the mood of the patient for the worse.

The first stage, is to manage their anxiety and hyperreactivity. While it is easier to manage with experience, when you first encounter patients like this, often it is baffling why a straightforward maxillary bicuspid infiltration seems so much more painful than it has the last 50 times you did it. Thankfully, with adequate anestheia and time, these patients nearly always reset before you have to start treatment.

Some thoughts on the administration of local anesthesia:

Topical anesthetics can be effective. More potent topical anesthetics have proven, in my clinical experience, to be more effective. Great care must be taken not to allow the topical to get into the saliva or to be swallowed. Under a rubber dam, the sensation a numb throat is not a good thing. For maximum effect, dry the area that the topical is going to be applied to and gently massage the topical into place using a cotton tip applicator. Within a minute or two, the maximum effect will be achieved. Again, make sure this topical is not solubilized in saliva and swallowed.

Make an effort to prevent patients from looking directly at the needle. Just seeing it can induce anxiety.

Pull the tissue tight prior to injecting.

Using different types of local anesthesia can be advantageous:

Buffering of local anesthesia will reduce the discomfort felt from the injection. This is one way of using local anesthetics with a vasoconstrictor without the concommitant discomfort from the acidity thereof.

Use of plain anesthetics (I like 4% Prilocaine or 3% Mepivacaine) will reduce the discomfort felt from the injection. Following this up with a local anesthetic with vasoconstrictor will provide more profound and longer lasting anesthesia again without the aforementioned discomfort.

Warming of local anesthesia will reduce the discomfort felt from the injection.

Use a combination of block anesthesia and supplemental injections whenever possible. There is no reason to rely on one or the other. In the most commonly treated teeth, the maxillary first molar and the mandibular first molar, there is clear evidence that supplemental injections will increase your success rate.

Allow adequate time for the anesthesia to take effect.

Whenever possible, use bony landmarks for injections. In the case of the Inferior alveolar nerve block, I try to locate the anterior border of the ramus and the head of the condyle before injecting.

For intraligamentary injections, intrapulpal injections and palatal infiltrations, I use 2% Lidocaine 1:100,000 epinephrine. I have seen negative sequelae to all three types of injections when Septocaine has been used. I have no reservations about using Septocaine for any other type of injection.

I no longer use intraosseus anethesia. While I have not personally experienced negative sequelae from this method of administration, I have seen the aftermath. While there may have been other contributing factors in each of these cases, I no longer use the technique.

Intrapulpal anesthesia is an effective adjunct, but should be used sparingly if at all in nonvital cases.

Secondary to any intraligamentary injection, some occlusal adjustment is necessary. While I often include occlusal adjustment as a part of my treatment protocol, I am a little more aggressive when I have administered these injections.

When delivering acute care, once adequate anesthesia has been achieved, focus on relieving the symptoms as quickly as possible. In a vital tooth, you want to make sure a pulpotomy is completed and then proceed apically from there. Long standing inflammation can make patients difficult to get numb, but also difficult to keep numb. Multiple visits are usually the best approach for patients in acute pain.

I wanted to address one final idea before concluding and one I always keep in mind.

Much of the research regarding anesthesia in endodontics comes from the Ohio State University. In a recent article, inferior alveolar nerve block injections were coupled with accessory(buccal infiltration, intraligamentary, and intraosseous) injections and administered to patients suffering from irreversible pulpitis in the lower first molar. These injections were administered under the supervision of the foremost authorities on anesthesia in endodontics. In the end, they were still unable to treat all of the patients in the study pain free.

The reason I mention this, is that expectations have to fit with reality. If not, you will live with a perpetual sense of disappointment. I treat people every day who have had toothaches. For some the condition is acute, for others it has been an ongoing phenomenon. Most teeth we treat whether it is in the initial stages of irreversible inflammation or if it is fully necrotic, have induced long term changes in the nerve that innervates it. Long term inflammation also effects the pH of the periapical tissues. This inflammation affects both the amount of local anesthetic that is free to affect the nerve as well as the ability of the local anesthetic to penetrate the nerve sheath. With all of that said:

There is nothing wrong with aspiring to make sure every patient is as comfortable as possible.

Every available means should be utilized to minimize discomfort during endodontic treatment.

It is essential that patients and practitioners alike understand that there are limits to our ability to anesthetize patients for endodontic treatment.

Understanding those limitations is fundamental to achieving superior outcomes.

Go Huskies!

Truely said

Thanxs doc for sharing your experiences