In the world of endodontics and endodontic treatment, the appearance of a sinus tract is to many an ominous sign. A patient recently referred to my practice had been advised by another dental specialist that a lower molar that tested necrotic and had a sinus tract and a significant periodontal probing had a poor prognosis. After treating these teeth for a long time, I did not believe that to be the case for this tooth. There are a lot of factors here that need to be considered, but in my experience these are some of the most predictable cases that I treat.

One of the most common presentations associated with necrotic teeth is the presence of periodontal destruction secondary to pulpal disease. The tooth typically is not painful, but exhibits a recurring swelling that expands then bursts repeatedly. Sometimes it has a dome shaped growth that doesn’t change much at all, but allows for the passage of fluid from the site of the infection. This swelling or growth is often associated with a signficant periodontal probing. The diagnosis in each of these cases is as follows:

Necrotic Pulp

Chronic apical abscess

These cases present several challenges but as is nearly always the case, with proper documentation and patient education, these cases can be handled successfully. The first thing to do is to diagnose the disease process accurately. This means collecting all available data to determine what you will see prior to starting treatment.

This can not be done in a single diagnostic visit.

You can collect information, you can collate data, you can assess radiographs and perform clinical evaluations but you cannot diagnose this case type with absolute certainty in a single visit. Fortunately, we don’t have to.

One of the benefits of multiple visit endodontic treatment is the ability to reevaluate patients without the completion of treatment. I am a believer that treatment of these teeth involves physical completion of instrumentation and obturation, but also of soft tissue resolution. This means the sinus tract disappears and the overlaying tissue normalizes. Once this is seen, I feel confident that the original problem has been resolved.

I could spend all day discussing this, but I want to start with a couple of cases that did not resolve.

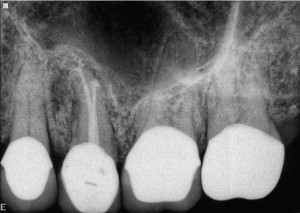

Case #1:

Tooth #14-Necrotic Pulp, Chronic Apical Abscess. The most notable symptom on this case preoperatively was tenderness to apical palpation on the buccal surface.

After a single initial treatment visit, the sinus tract resolved but the tenderness to palpation remained.

This same point tenderness on the buccal surface near the apex persisted through nonsurgical retreatment with calcium hydroxide as an intracanal medicament over a period of months.

Surgical exposure showed the buccal apices of tooth #14 located outside of the cortical plate. After resection that shortened the buccal roots to an infrabony terminus, the symptoms resolved completely.

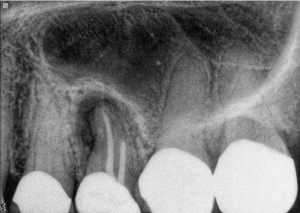

Case #2:

Tooth #13-Necrotic Pulp, Chronic Apical Abscess.The most notable symptom in this case was the persistent sinus tract.

After initial treatment this sinus tract did not resolve.

After nonsurgical treatment this sinus tract did not resolve.

Upon surgical exposure, a lesion was discovered. This lesion appeared contiguous with the root apex, and was removed nearly in toto. This lesion was intertwined with a 2mm x 3mm x 3mm section of necrotic bone. After the removal of this bone fragment, the sinus tract resolved completely.

Now looking at these cases, you would say, treating these cases doesn’t seem predictable at all. Both of these cases required surgery, how is that a success? Was my colleague correct in assessing these teeth as having a poor prognosis?

I don’t think so. But you’ll have to wait fo the next installment to find out why.