Root canal treatment has a tremendous success rate. Endodontic literature often suggests success rates in excess of 90% for initial endodontic treatment. However, even at 90% success, with over 16 million nonsurgical root canals being performed annually in the United States, that would be over 1 million root canals per year in the US that will eventually require further treatment.

A number of factors may contribute to the failure of endodontic therapy. Incomplete canal preparation, severe iatrogenic incidents, and inadequate postoperative restoration may all lead to a situation in which nonsurgical retreatment of a tooth is necessary. One of the most common causes for root canal failure is missed anatomy. The operator who performs endodontic therapy has to consider all probable anatomical configurations based on what is seen clinically and radiographically. It is also important to consider what anatomical anomalies are most common in the specific tooth you are working on. Ruling in or out the presence of anatomical variants is a key part of endodontic access. Untreated root canal systems may harbor bacteria, provide sustenance for bacterial growth, and allow diffusion of substances to the periradicular tissues that promote inflammation.

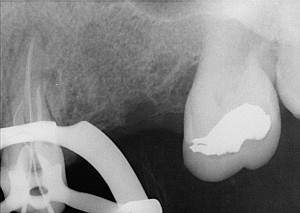

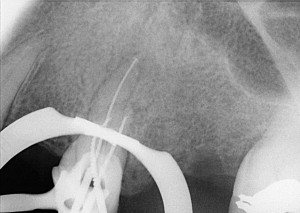

Use of preoperative radiographs is one of the first steps to attempt to locate all canal systems present. The symmetry of the root canal systems relative to the external root form is one clue. Use of the SLOB rule is another. For those unfamiliar, SLOB stands for Same Lingual Opposite Buccal. If the vertical angulation of the xray tube head is consistent in multiple radiographs, then when two structures are superimposed in the line of one radiograph, the more lingual or palatal canal/structure will follow the horizontal direction of the tube head when a shift radiograph is taken, while the more buccal canal/structure will seem to move in the opposite direction.

The following case is not an atypical presentation when dealing with a failing root canal. This gentleman was initially treated in South America and had initial endodontic treatment performed there. This tooth remained asymptomatic for a couple of years, but began to seem “tender” and “slightly irritated” according to the patient. During an extended visit to the area, the irritation began to subside, but the patient felt like the gum and tooth had begun to swell. He was taken to his cousin’s dentist, and was referred for evaluation. Upon initial presentation, the following clinical signs were noted:

Prior Endodontic Therapy

Type II Diabetic

Vital signs normal

Nonresponsive to Endo Ice on #13

No swelling noted on facial of #13

Positive response to percussion #13

Positive response to palpation on #13

Partial Denture Abutment #13

Diagnosis: Previously treated, Symptomatic apical periodontitis

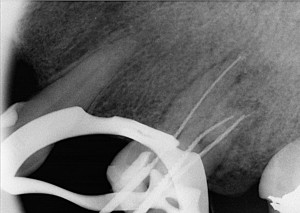

In the initial radiographs, the first periapical radiograph was taken, followed by a deliberate shift to attempt to identify missed anatomy. After anesthesia and rubber dam isolation, the access preparation was completed. Using the Dental Operating Microscope at approximately 11x, the prior restoration was removed, and a heat source was used to remove the gutta percha to the level of the orifices. Upon doing so, a small depression on the mesiobuccal was visually detected. Upon exploration with hand files, initial negotiation was performed in the mesiobuccal canal.

After working for a measure of time using precurved hand files, patency was achieved on the mesiobuccal system. The other canals were cleaned and shaped, and all of the canals were fuly prepared to working length.

Upon completion of instrumentation, calcium hydroxide was placed. The patient rescheduled the next visit, so approximately one month passed between appointments. The tooth no longer responded to percussion or palpation. After anesthesia, isolation and removal of the provisional restoration, Citric Acid, followed by Saline, Hypochlorite, Saline, EDTA, Saline and Hypochlorite as the final rinse were used to irrigate the canal(in that sequence). The master cones were fit, and the canals were obturated.

The tooth was restored using composite, and the partial denture was used to shape the disto-occlusal surface of the tooth to ideal contour. After minor adjustments to the restoration, a final radiograph was taken.

So many times, when endodontics is discussed, the emphasis is on the instrumentation or obturation techniques utilized. As impeccably as these canals may be shaped or filled, emphasis on these factors does not on any level address the failures associated with missed anatomy. The use of magnification, and the identification of possible anatomical configurations preoperatively are two tremendous weapons that can be used in nonsurgical retreatment.