There is a longstanding debate in the professional community of which is better: one visit or two visit endodontic treatment. I am asked this from time to time, most often from patients who have had prior endodontic treatment. The answer is, it depends on the tooth. I have a number of cases I want to discuss, with the hope that I can provide some clarity as to how I treat these cases and why.

In the first case, this patient presented to me with discomfort in an upper premolar.

Root canal therapy had been performed on this tooth several years prior on tooth #4 and the patient developed acute symptoms. Our software, TDO, allows me to collect data and organize it in a very thorough manner. In this case here is what the MTI (Multiple Tooth Information Page) looked like:

As you can see, the diagnosis on tooth #4 is:

Previously treated

Symptomatic apical periodontitis

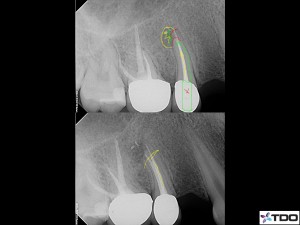

In addition, I am fortunate to have the ability to illustrate directly on the radiographs what our treatment objectives are and what the current condition of the patient is. I think it is imperative that patients be given information regarding their care. It is much more fulfilling for patient and provider and we must work together as a team to obtain superior outcomes. It also gives patients an opportunity to ask questions, and gain a better understanding of just what “is taking so long”!

When evaluating an acute retreatment case of this sort, my biggest priority is to obtain patency. The reason is simple. What is the cause of the discomfort in this case? Not the cause of the failure, but the acute cause that has the patient in my office at this time.

Pressure.

Pressure is a phenomenon that is rarely discussed, but all too relevant to me as an endodontist. Without getting too technical, when these situations turn acute, there are a number of factors that must be addressed, but paramount is the need to relieve discomfort. To do this, a pathway must be made to reduce the pressure apically.

The microscope is a large benefit in these cases as it allows me to get a lot of light into the working field. It also allows me to differentiate materials from one another deep within the tooth. This minimizes iatrogenic events. In this case, a tooth colored material had been used as a buildup. After removal of the restorative material, we were able to locate the orifices and start retreatment. Patency was obtained, and copious irrigation with Sodium hypochlorite was performed. I refined the canal preparations and because I did not observe active drainage, I placed calcium hydroxide and a provisional restoration. The patient was given analgesics as well as an antibiotic.

Her symptoms continued to improve over the next few days, and she remained asymptomatic for the following four weeks. At her next visit, we removed the Calcium hydroxide using EDTA and an Endoactivator. The tooth was obturated and restored with two stainless steel posts.

Could this case have been done in one visit?

Yes.

Do I think I could have obtained the same technical outcome?

Yes.

Why did I choose to do this case in two visits?

Pressure is what was creating the acute situation. By relieving the pressure immediately and allowing it to remain lower through the next few days by not obturating the case, the patient was more comfortable. In addition, I had the ability to discern that for a long period of time prior to her obturation visit, she was without discomfort. The best predictor of postoperative pain is preoperative pain. When we are dealing with a crown we are trying to save and multiple posts placed in an effort to prevent snap off, the last thing I want is persistent apical tenderness that requires nonsurgical retreatment. The alternative would be to perform apical surgery on the tooth.

While these options for revision are always a later possibility when endodontic treatment is performed, the ability to render a tooth free from symptoms prior to obturation is ideal. It is my hope that this will minimize the need for additional procedures.